On a trip to Lyon, France, Christine Roberti frequents bustling cafes, samples gourmet desserts and French cheeses at a renowned food hall and enjoys multi-course lunches and dinners at a handful of Michelin-starred spots—only to find that the heart of Lyonnaise cuisine truly lies in the city’s homey bouchons.

In the fall of last year, I travelled to France for the first time.

Fresh off the season four finale of Emily in Paris, the carryon I packed for my weeklong trip was crammed full of heels (nevermind the cobblestones), a lot of faux leather, and a Yves St. Laurent lipstick or three. But shopping in the country’s dreamy capital city wasn’t why I was going.

In fact, the closest I actually got to seeing Paris and living out my TV fantasy was munching on a pain au chocolat and ungraciously chugging a latte at 7 a.m. inside the Gare du Nord train station, while waiting for my connection to Lyon.

The third largest city in France, Lyon, capital of France’s Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region, is framed by the Rhône and Saône rivers and is home to UNESCO World Heritage designated Roman ruins that can be found all over its old city centre, along with breathtaking architecture at every turn. But Renaissance charms aside, the city also proclaims to be the “gastronomy capital of the world”, with more than 4,000 restaurants packed into its 48 km2 parameters—88 of which are included in the Michelin Guide, with five two-star and 13 one-star establishments. In fact, Lyon is home to the second largest number of Michelin-starred eateries in all of France, falling just behind Paris, with an outstanding count of 144.

The culinary journey begins

Getting to Lyon from Paris was easy—high-speed trains depart Gare du Nord frequently and the travel time is just under two hours.

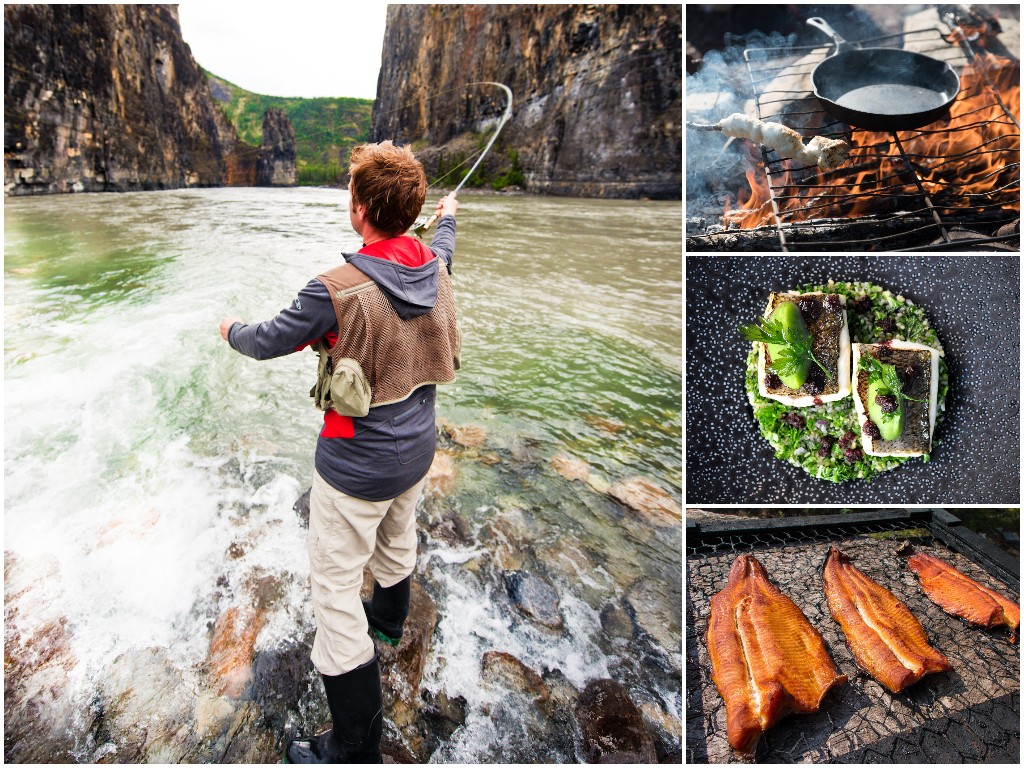

On a mission to try some Lyonnaise specialties, like the famous tarte à la praline made with crushed pink pralines (you can only find it in Lyon) to saucisson de Lyon, a traditional sliced pork sausage made with pistachios, my first stop was Les Halles de Lyon Paul Bocuse, an indoor gourmet food hall that’s become one of the city’s largest tourist attractions for foodies seeking out the best in French cuisine.

First opened in 1859, the original covered market came from humble beginnings, and was largely a space for trading fresh produce and staples like eggs and produce. A century later, the market was revitalized, and in 1971, given its current name, as tribute to one of Lyon’s most celebrated chefs, Paul Bocuse. Today, more than 60 specialty vendors hawk goods from their stalls to the roughly 10,000 visitors the food hall receives daily. Here, you’ll find everything from the finest line-caught seafood, to dainty desserts too pretty to eat, to whole refrigerated hens and hares—snow white feathers and furs still intact, a somewhat tragically beautiful way to validate the pedigree of the breed.

Spoiled for choice, I quickly learned it’s impossible to go hungry in this city. The options are endless, and I’d be remiss to not visit at least one Michelin spot on my trip, given the abundance of star-worthy establishments.

Michelin mania

A casual midday lunch at Le Grand Réfectoire unveiled elevated takes on Lyon staples, including a thinly-sliced and expertly plated version of Lyonnaise sausage with pistachios, served cold and topped with crunchy popcorn, pine nuts and creamy cheese. Next came an impressively stacked grilled eggplant atop a poppyseed-crusted slab of salmon, served on a buttery bed of crisp green beans layered in a Dijon mustard.

And finally, the dessert—the most delicate chouquette layered with Chantilly cream and crunchy caramelized peanuts—that disappeared in a mere two bites. Awarded a Michelin plate in the 2020 and 2021 Michelin Guide France, the menu, dreamed up by two-Michelin star chef Marcel Ravin of Blue Bay in Monte Carlo, hit all the right notes as far as a typical Michelin dining experience goes.

Looking for local

But much like Ireland has its snug pubs, and Colombia has its lively bodegas, I had to find out—where do you go in Lyon if you just want good, old fashioned comfort food?

As it turned out, the answer lies all around the city. Bouchons, which first began appearing at the end of the 19th century, are traditional restaurants found only in Lyon. Decked out in checkered red-and-white cloths, the wooden tables are set close together, creating an atmosphere rich for conversing with your neighbour over a bottle of wine and a hearty, homecooked meal.

The food is always simple, but overwhelmingly culturally rich—housemade duck pâté, salad Lyonnaise, coq au vin and warm apple desserts are all staples. Warm lighting and a tight-knit interior add to the cozy factor, and it’s not uncommon for the chef to pop out and chat with the guests.

Bouchons, though rustic in their origins, take great pride in respecting culinary heritage, using the freshest, seasonal ingredients and local products, and abiding by homecooked meals that follow original recipes.

It’s this simple formula for success that fuels repeat business by locals and tourists alike.

In 2012, the Lyon Chamber of Commerce and Industry created a label exclusively for restaurants that identify as a “Bouchon Lyonnais” to place in their windows, alerting diners that an exceptionally authentic meal lies ahead. Consider it a friendly guarantee that inside, the dishes are always homemade and follow Lyonnaise cooking methods.

Because as with anything exceptionally authentic, everybody wants a piece—especially in the gastronomy capital of the world.

This story first appeared in the Spring 2025 issue of Culinary Travels Magazine. Click here to subscribe to the magazine. Click here to view the digital magazine.